The Warrant said text messages. The report said photos were in “Plain View”

Somewhere between those two, the Fourth Amendment got blurred.

In courtrooms across Texas, defense attorneys are increasingly confronted with search warrants that start narrow but end broad. A warrant authorizes the search of a phone for “text messages between the defendant and the complainant,” yet the resulting forensic report includes hundreds of photographs, text messages between other parties, and location data — all justified under the phrase “plain view.”

That phrase carries authority, but also danger. The plain view doctrine was originally written for an officer standing in a room, not an examiner scrolling through a terabyte of data. And when it’s misapplied, it risks turning every digital device into a constitutional black hole. Courts fail to recognize what plain view in a phone or computer actually looks like.

Let’s unpack what plain view really means under Texas law, why it breaks down in the digital age, and how defense counsel can recognize, and challenge, its misuse. Specifically, this playbook explains what plain view really requires under Texas and federal law, why it rarely applies in digital forensics, and how to spot (and suppress) overreach before it reaches a jury.

Understanding General Searches of Digital Data & How Law Enforcement tries to sidestep this with Plain View

The Fourth Amendment was written to prevent exactly what digital forensics now tempts: general searches. It prohibits warrants that leave to the discretion of the officer “the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” U.S. Const. amend. IV. This particularity requirement, which was born out of the Founders’ rejection of British “general warrants” and writs of assistance, remains to this day the line between lawful investigation and unconstitutional intrusion.

Digital evidence pushes that line to its limits. A single phone or laptop can hold years of personal messages, photos, banking records, health data, and private communications. That volume of information makes the risk of a general search exponentially higher. When an examiner opens an entire Cellebrite extraction or browses freely through unrelated folders, the search stops being specific, and it becomes a digital equivalent of rummaging through every drawer in the house just to see what turns up.

Just to be clear, the Fourth Amendment prohibits general search warrants and requires that warrants describe, with particularity, the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized. U.S. Const. amend. IV.

Key Insight:

"Regarding computers and other electronic devices, such as cell phones, case law requires that warrants affirmatively limit the search to evidence of specific crimes or specific types of materials." Diaz v. State, 604 S.W.3d 595 (Tex.App.-Hous. (14 Dist.), 2020) aff'd, 632 S.W.3d 889 (Tex. Crim. App. 2021).

The particularity requirement is intended to protect people from "general, exploratory rummaging in a person's belongings," Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443, 467 (1971), and to ensure that a search conducted by law enforcement be "carefully tailored to its justifications," Maryland v. Garrison, 480 U.S. 79, 84 (1987). The lawful scope of any search is defined by what officers are looking for and where there is probable cause to believe it can be found. United States v. Ross, 456 U.S. 798, 824 (1982). In the digital context, that means investigators must confine their examination to data that relates directly to the crime described in the warrant affidavit.

As the Texas Court of Appeals explained in Diaz v. State, 604 S.W.3d 595, 605 (Tex. App. 2020), a search of computer records is constitutionally valid when it is narrowly limited to evidence connected to the specific offense under investigation.

"When investigators fail to limit themselves to the particulars in the warrant, both the particularity requirement and the probable cause requirement are drained of all significance as restraining mechanisms, and the warrant limitation becomes a practical nullity." Long v. State, 132 S.W.3d 443, 447-48 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004). "Obedience to the particularity requirement both in drafting and executing a search warrant is therefore essential to protect against the centuries-old fear of general searches and seizures." United States v. Heldt, 668 F.2d 1238, 1257 (D.C.Cir.1981).

"A search is unreasonable and violates the protections of the Fourth Amendment if it exceeds the scope of the authorizing warrant." DeMoss v. State, 12 S.W.3d 553, 558 (Tex. App.-San Antonio 1999, pet. ref'd). Fruits of such a search cannot be "admitted in evidence against the accused on the trial of any criminal case" unless the fruits were "obtained by a law enforcement officer acting in objective good faith reliance upon a warrant issued by a neutral magistrate based on probable cause." Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 38.23. Whether a search exceeds the scope of the authorizing warrant requires a Fourth Amendment reasonableness review-a question we review de novo. See Hereford v. State, 339 S.W.3d 111, 118 (Tex. Crim. App. 2011); State v. Powell, 306 S.W.3d 761, 769-70 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010).

Despite these clear constitutional guardrails, law enforcement often seeks to justify broad, exploratory searches of digital data by invoking the plain view doctrine. What begins as a warrant limited to text messages or specific communications can quickly expand into a review of photo libraries, cloud backups, or unrelated applications with each step taken under the claim that the evidence was in “plain view.” But digital evidence isn’t like a gun on a table or drugs on a counter. Every file, folder, or app must be intentionally opened, and nothing is “seen” without a deliberate act of access.

When investigators cross that line, calling it “plain view” doesn’t cure the overreach rather, it rebrands a general search as something it is not. And the Constitution still calls what it has always been: unreasonable.

What Plain View Was Meant to Be

The Plain View doctrine is a well-established exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement, permitting law enforcement to seize evidence not specified in a warrant if three conditions are met:

- The officer is lawfully present where the evidence can be viewed;

- The officer has a lawful right of access to the object; and

- The incriminating nature of the evidence is immediately apparent.

These instances are well articulated in Texas and federal case law, including Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443, 91 S.Ct. 2022, 29 L.Ed.2d 564 (1971); Joseph v. State, 807 S.W.2d 303 (Tex. Crim. App. 1991); Lee v. State, 04-24-00188-CR (Tex. App. Sep 30, 2025) In other words, if an officer is lawfully in a home and sees contraband in plain sight, they may seize it even if it wasn’t named in the warrant. But plain view is a doctrine of sight, not search. It authorizes seizure of what’s visible, not exploration for what might be hidden.

If, during that lawful observation, an officer encounters evidence that suggests a separate crime or the likelihood of additional contraband, the Constitution doesn’t give license to keep searching rather it demands restraint. At that moment, the officer’s discovery establishes new probable cause, but not new authority. To lawfully continue searching beyond the scope of the original warrant, the officer must stop, secure the scene, and obtain a new warrant supported by that fresh probable cause. Failing to do so transforms a legitimate seizure into a general search, the very abuse the Fourth Amendment was written to prevent.

Real World Example of Plain View in a Physical Setting

To really understand how the plain view doctrine works, it helps to step away from screens and picture it first in the physical world.

Imagine officers executing a warrant to search a home for a stolen 50-inch television. They enter through the front door, methodically moving from room to room. The warrant allows them to look anywhere a 50-inch television could reasonably fit— that is, the living room, the den, maybe an attic assuming it could fit. They can check behind doors, under tarps, even in a large closet.

But that warrant does not grant permission to open dresser drawers, rifle through jewelry boxes, or pry open a locked safe. A television simply wouldn’t be there. Opening those spaces would turn a specific, court-authorized search into an unauthorized fishing expedition—which is exactly what the Fourth Amendment forbids.

Now picture this: while standing in the kitchen during that search, one officer notices a clear plastic bag sitting on the dining table across the room. Inside is a white powdery substance. Its incriminating nature is immediately obvious. The officer can seize that bag under the plain view doctrine, but that’s where his authority stops.

If he believes there may be more contraband hidden elsewhere in the home, the proper course is not to keep searching, but to stop. Secure the scene. Write a new affidavit explaining what was found in plain view. Then seek a new warrant authorizing a search for narcotics. That is the balance the Fourth Amendment demands. Plain view permits seizure, not expansion. It’s a moment of observation, not an invitation to explore. The doctrine was built to allow law enforcement to lawfully collect what is visible, not to wander into new searches under the guise of discovery.

When you picture the search of a house, the rules feel tangible because there are walls, doors, rooms, drawers, and other clear limits. You can see where lawful authority ends and intrusion begins. But digital devices erase those boundaries. Judges tend to think that inside a phone or laptop, there are no walls or locked rooms, only layers of data stacked invisibly beneath the surface. Each click is a doorway; each folder, a new search. And unlike a home, there’s no physical barrier to remind an investigator they’ve gone too far. Which is why, when the same “plain view” logic is carried into the digital world, the analogy breaks down entirely.

Why Digital Devices Break the Analogy

The reality is a phone isn’t a room — it’s an entire city. More than that, it’s an individual’s lifetime. Dare I say it should be more protected than one’s own house because of the privacy and potential for infringement on one’s Fourth Amendment rights.

Key Insight:

“A phone not only contains in digital form many sensitive records previously found in the home; it also contains a broad array of private information never found in a home in any form” Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 189 L.Ed 2d 430, 573 U. S. 373 (2014)

Every app is a building, every folder a floor, every message thread contained within a messaging application is a locked room with its own key. Opening one doesn’t “show” you the others. You have to decide to go there.

The Courts have recognized that electronic devices are “virtual warehouses of an individual’s most intimate communications and photographs,” United States v. Wurie, 728 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2013). This was, of course, superseded by Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 189 L.Ed 2d 430, 573 U. S. 373 (2014), in which Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. noted:

Key Insight:

“One of the most notable distinguishing features of modern cell phones is their immense storage capacity… The storage capacity of cell phones has several interrelated consequences for privacy. First, a cell phone collects in one place many distinct types of information—an address, a note, a prescription, a bank statement, a video—that reveal much more in combination than any isolated record. Second, a cell phone's capacity allows even just one type of information to convey far more than previously possible. The sum of an individual's private life can be reconstructed through a thousand photographs labeled with dates, locations, and descriptions; the same cannot be said of a photograph or two of loved ones tucked into a wallet. Third, the data on a phone can date back to the purchase of the phone, or even earlier. A person might carry in his pocket a slip of paper reminding him to call Mr. Jones; he would not carry a record of all his communications with Mr. Jones for the past several months, as would routinely be kept on a phone… According to one poll, nearly three-quarters of smartphone users report being within five feet of their phones most of the time, with 12% admitting that they even use their phones in the shower… Indeed, a cell phone search would typically expose to the government far more than the most exhaustive search of a house”. Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 189 L.Ed 2d 430, 573 U. S. 373 (2014)

That’s why State v. Granville, 423 S.W.3d 399 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014), is an important landmark in Texas. This case noted police may legitimately “seize” the property and hold it while they seek a search warrant. But they may not embark upon a general, evidence-gathering search, especially of a cell phone which contains “much more personal information ... than could ever fit in a wallet, address book, briefcase, or any of the other traditional containers that the government has invoked.” State v. Granville, 423 S.W.3d 399 (Tex. Crim. App. 2014).

Law enforcement may not rummage through its contents without judicial authorization. It is important to understand that digital searches aren’t passive; no, they’re deliberate. Every click, filter, or folder access represents a new investigative choice. Which means “plain view” in digital forensics should rarely happen by accident.

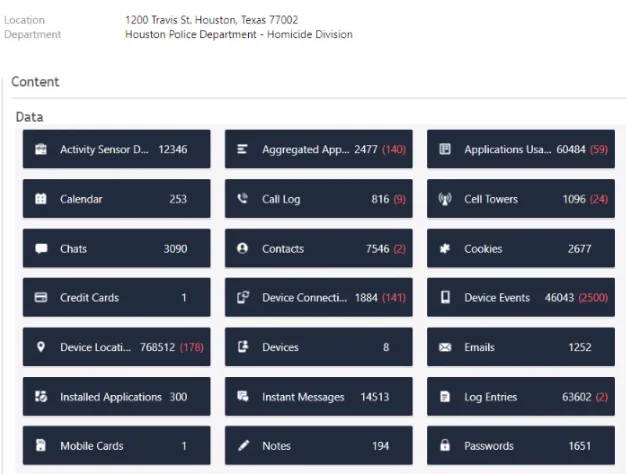

The Cellebrite Reality

Here’s what every defense attorney needs to know.

Key Insight:

These data sets are typically encapsulated in their own container with the occasional bleed-over. The examiner chooses which logical containers to open: text messages, photos, app data, browser history, and location logs.

When an examiner says they “stumbled across” something in plain view, it’s rarely a stumble. Cellebrite doesn’t randomly display evidence; it shows what the examiner commands it to show. Opening a new folder, viewing a new app, or expanding to a new dataset is an intentional act. It’s a new search. If we equate it to the physical setting noted above, it’s an examiner choosing to open the drawer even though it cannot possibly contain a 50” television.

This is particularly true when a warrant authorizes examination of “text messages between Defendant and Victim,” yet the examiner browses through the Photos directory. At that point, the search is no longer within “plain view” and it violates the defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights. United States v. Morton illustrates this point well. Even when granting broad deference to magistrates, courts cannot presume probable cause extends to every file type on a device. The panel recognized that probable cause existed to “search Morton’s contacts, call logs, and text messages,” but not his photos. United States v. Morton, 984 F.3d 421, 427–28, 431 (5th Cir. 2021) (“the magistrate did not have a substantial basis for determining that probable cause existed to extend the search to the photographs on the cellphones”). Although Morton was later granted rehearing en banc and vacated, its reasoning remains instructive. In the subsequent opinion, the Fifth Circuit noted that Morton’s new argument—that good-faith should be analyzed separately for each area searched—was forfeited because it had not been raised in the district court or in his original appellate brief. United States v. Morton, 46 F.4th 331, 338–39 (C.A.5 (Tex.), 2022).

There must be a substantial basis to search each “drawer” — and, in that case, photographs— and without it, the search is unconstitutional. Specifically, the court found that extending a search to areas of a device (such as photographs) without a substantial basis for probable cause was unconstitutional. It is important to note that this decision was later vacated by United States v. Chandler, 571 F.Supp.3d 836 (E.D. Mich. 2021), which limits its precedential value. Nonetheless, the underlying principle is that probable cause must support each area of a digital device to be searched.

The “Plain View of Photographs” Problem

One of the most common overreaches that we typically see in modern Law Enforcement forensic practice looks like this:

- The warrant authorizes a search of text messages between two parties.

- The forensic examiner accesses Photos and Videos under the “guise” of verifying message attachments.

- Upon encountering unrelated images, the examiner flags them as “plain view.”

This logic collapses under scrutiny.

- Lawful Presence? No — the examiner left the authorized dataset. He will argue he was accessing a photo attached to a message, but when done within Cellebrite the examiner is taken directly to the photograph, so it becomes very difficult to see other photographs.

- Lawful Presence? No — the warrant covered messages, not the photo library.

- Immediately Apparent? Rarely — most thumbnails are too small or out of context to make the incriminating nature immediately apparent and obvious without additional manipulation of the photograph (e.g. think extended manipulation of item in a pocket during a pat down). In cases where he was lawfully present, the examiner would still need to articulate how it became immediately apparent. Furthermore, it becomes difficult to make claims of immediate apparentness for items that are not a photograph – such as text message communications with other parties.

In short, it fails all three prongs. As Villegas v. State and Diaz reaffirm, warrants for digital devices must affirmatively limit searches to evidence of specific crimes. Opening unrelated folders or apps transforms a lawful search into an unreasonable and unconstitutional one.

All of this doesn’t mean that plain view can never exist in the digital world, rather only that it almost never happens by accident. At Black Dog Forensics, we are of the belief that true digital plain view is rare, deliberate, and immediately recognizable when it occurs. It’s the moment when an examiner, operating fully within the lawful scope of a warrant, encounters something unmistakably illegal that appears without further exploration or expansion of the search.

In those instances, the Constitution doesn’t require blindness; rather, it requires discipline. The correct response is to stop, preserve what was seen, and seek new judicial authorization before proceeding.

True Plain View Example

Here’s a real case from my own work where plain view was unmistakable.

Here is the background: a suspect in multiple robberies was captured on CCTV photographing several banks leading up to various robberies. Surveillance footage showed the individual taking pictures consistent with planning a robbery and casing the locations. I first obtained warrants for historical cell-site and geolocation data around several of the robberies. Those tower dump records produced corroborating hits that tied the same device(s) to each location. With that foundation, I secured a second evidentiary search warrant for the suspect’s phone to search for location data, relevant messaging (he operated with others), and photographs/videos.

While lawfully reviewing the photo dataset authorized by the warrant (satisfying lawful presence and lawful access), I encountered images that were immediately and unmistakably apparent as child sexual abuse material (CSAM). There was no need to zoom, enhance, manipulate the photograph, or consult metadata. The criminal nature was obvious upon sight. At that moment, I stopped the search because I immediately knew I found images of children engaging in sexual intercourse. The device was secured. I obtained a new warrant before conducting any further analysis, including even the original search of robbery evidence.

That is what true digital plain view looks like:

- Lawful presence within the specific data container is authorized.

- Immediate apparentness of illegality without further manipulation.

- Prompt cessation and judicial reauthorization before any expanded search.

Contrast that with the misuse of “plain view” to excuse broad fishing expeditions through apps and data never named in the warrant. The difference isn’t technical, it’s constitutional. Plain view permits seizure of what is seen, not expansion of scope.

Key Insight:

When the “view” ends, the warrant must begin again.

Red Flags To Look Out For

Defense counsel should be alert for indicators that the plain view doctrine is being used as a post hoc justification for overbroad searches:

- Government or State is using Evidence from data types not listed in the warrant (e.g., Photos, Notes, Messages between parties not asked for, Etc.)

-

Plain view was located as a result of:

- Global keyword or hash searches run across the entire extraction.

- Verifying a photograph in a message thread.

- Review of discovery shows no request for a second warrant and multiple instances of “plain view” evidence after the initial finding.

- “Plain View” noted only in narrative form, without supporting screenshots documenting the said “Plain View”.

- Reports state that evidence was “in plain view” in directories that required deliberate navigation.

Each of these red flags can become the foundation of a suppression motion with a clear explanation of how said items are in fact “containers” equivalent to a drawer that should have never been opened.

The Defense Playbook

- Obtain Everything. Request the search warrant, supporting affidavit, full Cellebrite.ufdr or .zip extraction, and examiner notes.

- Map Scope vs. Action. Compare the warrant’s limits (data type, date range, accounts) to the examiner’s actual steps. If the item found in “plain view” was from opening an app, folder, or time period outside that scope, that’s a violation.

-

Challenge the Doctrine’s Prongs.

- Presence: Were they in the authorized container?

- Access: Did the warrant cover that data type?

- Immediacy: Was the content clearly incriminating on sight, or only after manipulation?

- Argue the Duty to Stop. Once outside-scope data was encountered, law enforcement should stop and seek a new warrant. Continuing the search might invalidate the plain view claim. Remember, a phone is not a car.

- Move to Suppress. Frame the motion as exceeding warrant scope, lacking nexus, or violating the immediacy and access requirements under Texas and federal law. Work with Black Dog Forensics to truly articulate this so we can show that the officers actions were not in good faith the evidence must be suppressed.

What Black Dog Forensics Brings to the Table

At Black Dog Forensics, we operate on a simple principle: integrity in process equals credibility in evidence. Our examiners document every action taken during analysis. We routinely review opposing counsel discovery, expert reports, logs, and extractions to determine whether searches stayed within the lawful scope of the warrant.

For defense attorneys, that means actionable insight:

- Discovery Review: comparing all discovery and warrant language to examiner activity and evidence obtained.

- Technical declarations: explaining why “plain view” doesn’t apply to deliberate navigation. Furthermore, it’s helpful to illustrate this to a judge with a video walkthrough so we can defeat the “good faith” argument. Hard to say obtained data was in good faith when the officer went looking for it outside of their scope (e.g. opening the drawer to look for the 50” TV).

- Expert testimony clarifying what digital “plain view” actually is and what it is not.

The plain view doctrine was never meant to authorize limitless exploration. It was meant to capture what an officer happens to see while standing lawfully where they’re allowed to be.

Key Insight:

When courts understand how digital forensics really works, and more importantly how digital data is compartmentalized, they recognize how easily “plain view” can become plain abuse.

Rember, a phone isn’t an officer standing in the middle of a living room. Digital forensics doesn’t work that way. Typically speaking, nothing on a phone or hard drive is “plain view” until someone decides to open it. Every tap, every folder, every search is a choice that carries constitutional consequences.

When the view stops being plain, the warrant must start again.

If your case involves a claim of digital evidence found “in plain view,” let Black Dog Forensics help you determine whether what they saw was ever truly in view.

References

1. U.S. Const. amend. IV.

2. Diaz v. State, 604 S.W.3d 595 (Tex.App.-Hous. (14 Dist.), 2020) aff'd, 632 S.W.3d 889 (Tex. Crim. App. 2021).

3. Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443 (U.S.N.H., 1971).

4. Maryland v. Garrison, 480 U.S. 79, 84, 107 S.Ct. 1013, 94 L.Ed.2d 72 (1987).

5. U.S. v. Ross, 456 U.S. 798 (U.S.Dist.Col., 1982).

6. Long v. State, 132 S.W.3d 443, 447–48 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004).

7. U.S. v. Heldt, 668 F.2d 1238 (C.A.D.C., 1981).

8. DeMoss v. State, 12 S.W.3d 553 (Tex.App.-San Antonio, 1999).

9. Art. 38.23. Evidence not to be used, TX CRIM PRO Art. 38.23.

10. Hereford v. State, 339 S.W.3d 111 (Tex.Crim.App., 2011).

11. State v. Powell, 306 S.W.3d 761 (Tex.Crim.App., 2010).

12. Joseph v. State, 807 S.W.2d 303, 308 (Tex.Crim.App., 1991).

13. Lee v. State, 2025 WL 2808343 (Tex.App.-San Antonio, 2025).

14. Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373 (U.S.Cal., 2014).

15. U.S. v. Wurie, 728 F.3d 1 (C.A.1 (Mass.), 2013).

16. State v. Granville, 423 S.W.3d 399 (Tex.Crim.App., 2014).

17. United States v. Morton, 46 F.4th 331 (C.A.5 (Tex.), 2022).

18. Villegas v. State, 2018 WL 2222196 (Tex.App.-San Antonio, 2018).

346-200-6097

346-200-6097